In assessing the respective performance patterns of the Red Bull, Ferrari and Mercedes this season, a lot of attention has been focused on their differing aerodynamic traits and how these are better or worse suited to each track layout. But relatively little has been discussed about a performance factor that’s at least as significant: how each of the RB18, F1-75 and W13 uses its tires.

There are myriad factors feeding into tire behavior – notably weight distribution, suspension geometry, tire pressures and brake bias – but perhaps the most crucial of all is how the brakes are used to indirectly control the tire temperature via the wheel rims. It is an incredibly complex subject.

READ MORE: How does the F1 Sprint work? The format explained ahead of its return this weekend in Brazil

The tire’s optimum temperature (depending upon compound) is between 100-150 degrees C. The carbon brake discs run around six inches away at between 500-1,000-deg C. The requirement is to keep the tires within their quite narrow operating temperature window, which is trickier to do with the undriven front tires than the driven rears.

The focus with cooling of the rear tires is simply to divert the brake heat out and away from the wheel rim, but at the front sometimes it is advantageous to transfer more of that heat into the tires in order that they come up to temperature in time for a qualifying lap, a race start or restart.

Brake ducts are used to channel the air as required. Those at the front, because their task is more complex than those at the rear, tend to be of a more intricate design – and this is where we see a big variation between the Red Bull, Ferrari and Mercedes.

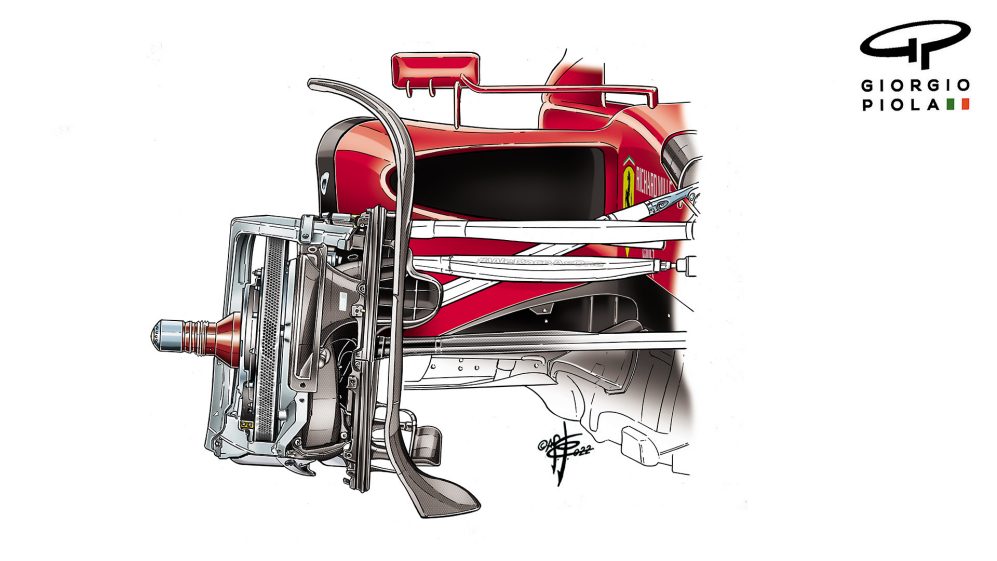

Red Bull’s full brake assembly after a fairing redesign, part of which was the removal of a thermal covering.

Furthermore, the complexity of demands for the ducts has increased this year because of the regulation stipulation of a standardized wheel rim. Previously, teams designed their own rims, with differing patterns of indentations on their inner surface to give different surface areas and therefore different rates of heat absorption, according to the demands of the track and the car itself.

Also new in the 2022 regulations is the requirement to exit the brake cooling air through a single rearwards-facing outlet rather than out through the wheel spokes, where it would previously help accelerate the out-washed airflow coming around the front tyres.

READ MORE: ‘There’s no limit to what we can do’ – Hamilton on fighting back, ‘best friend’ Wolff, and changing the world

The channels within the ducts apportion how much of the incoming air goes directly to the brake disc, to keep it below the critical threshold at which the carbon would oxidise. There will be another channel directing the air to the brake caliper. Both flows then exit through the same rearwards-facing outlet.

Encasing these channels is a big carbon fiber drum which is there solely to contain the heat within the brake area, preventing too much of it seeing through the metal wheel rim and into the tyres. As a rule of thumb, every 10-deg C of rim temperature increases tire temperature by around 1-deg C.

Inside their drum, Ferrari run without shrouding around the disc, unlike Red Bull or Mercedes.

Ferrari’s solution to this complex set of demands appears simpler than that used by Red Bull and Mercedes in that they have left the brake disc exposed within the big drum. On the other two cars, there are fairings within the area inside the drum which can be varied to apportion different flows to the disc, caliper and directly to the outlet.

From the respective performance patterns of the cars this season, it would seem that Ferrari’s system puts more heat into the rims and tires, in that it almost never struggles for instant first lap front tire performance – and the other two often do.

This could well be an important part of Ferrari’s super-strong qualifying performances this season. The downside, however, is that the rim temperature can continue to increase during a race stint, thereby overheating the tires.

READ MORE: ‘I always believed in the project’ – Max Verstappen on Red Bull, his second title and how long he plans to race in F1

We saw this trait as recently as Japan, where Charles Leclerc managed to hold onto Max Verstappen’s Red Bull for three laps, both lapping two seconds faster than the rest of the field, before the Ferrari’s front tires then began to overheat, allowing Verstappen to pull easily away and Sergio Perez’s Red Bull to catch up to the Ferrari by the end.

The phenomenon was also a factor in Verstappen’s defeat of Ferrari in the Imola Sprint race, Miami and Hungary.

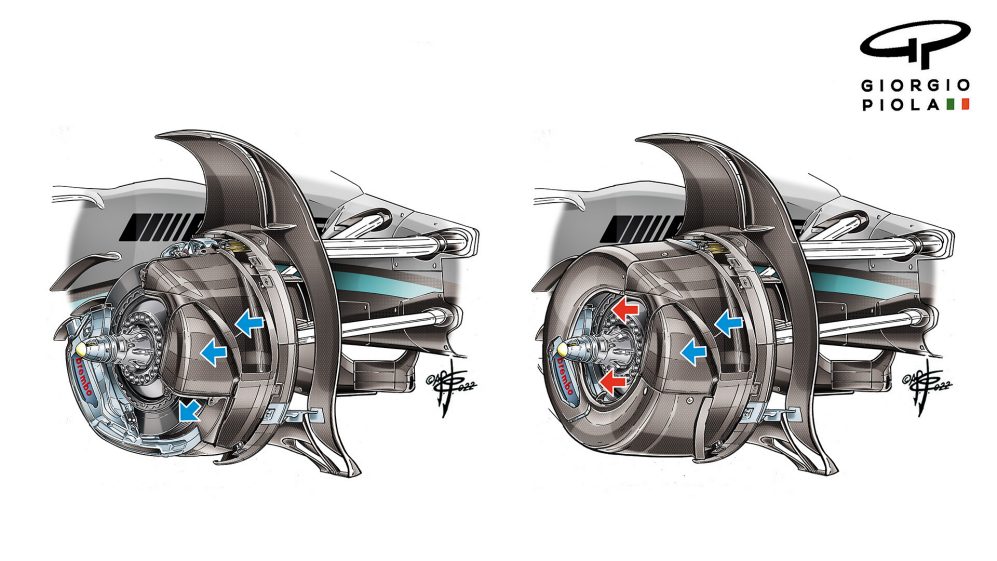

(L) Mercedes shrouding with the lower part open; (R) Mercedes shrouding with the lower part closed.

For much of the season it seemed as if Mercedes had the best front tire temperature cooling, typically with strong pace towards the end of stints. But the downside was that often the front tires would not be up to temperature by the beginning of a qualifying lap.

Red Bull seemed to straddle the positions of Ferrari and Mercedes: better than Mercedes in qualifying but not as good as Ferrari, with better tire life than Ferrari in the stints but not as good as Mercedes. Both Red Bull and Mercedes have improved their respective brake cooling compromises as the season has progressed.

It all underlines just how these differences have, under the new regulations, been accentuated in their importance to determining the competitive order.

Did you miss our previous article...

https://formulaone.news/mercedes/insane-f1-demo-lap-down-the-las-vegas-strip-