Formula 1 has changed dramatically over the last 30 years, so setting up a team is not quite as simple as it was for me with Jordan in 1990.

I started there in early January and worked for a month building the drawing office on the mezzanine floor above the F3000 race shop at Silverstone. I then sourced a few catalogs for bearings, hoses, nuts and bolts etc as, in reality, we had nothing. I also spent time setting up a few suppliers and trying to source a wind tunnel to use.

After convincing Andrew Green and Mark Smith to join me, they started at the beginning of March and from there the three of us started designing a car that we hoped to test in early November and race in the United States Grand Prix in Phoenix in early March the following year.

For Andretti Global, assuming it gets an entry for its Cadillac project, it isn’t going to be as simple as that. I’m not saying it was straightforward for us at Jordan, but it took significantly fewer people in the early stages to get a team up and running back then.

For Andretti, there are two main options at opposite ends of the spectrum. There’s the Haas way of partnering with a current ‘works’ team like Alpine. From what we know, Andretti intends to use the Renault power unit, so it would just be an extension of that agreement.

With this approach, you do everything the regulations allow you to do in terms of taking components from other teams. This cuts down on your initial set-up investment in equipment and makes it possible to survive with a workforce of around 300. But if you go down that route, you are in the hands of someone else and your performance will be hampered by how your technical partner team goes about its business.

Andretti has experience in operating this way as this is how it works now. The various series it competes in all use spec chassis from various suppliers and that limits the level of experience you require in your team. Yes, you still need a strong race team but it’s the other work required to create a car from scratch that multiplies the number of people you need.

The other route is to do it all yourself. But with the current cars and their complexity, that means you are talking about a workforce of a minimum of 600+ people. Also, by having facilities in both the USA and the UK, as Andretti plans to do, you will need some overlap of personnel. So that number is a minimum, you could easily add another 100 to that.

Recruiting so many people and, more importantly, getting them to pull in the same direction, is no easy task. It takes time, patience and a lot of money. Never mind where else money has to be spent, an annual wage bill for this amount of people could very easily exceed $40 million.

Over the years, we have seen various organizational approaches at various points between the common, and very functional, pyramid through to a more flat structure where decisions are made by committee.

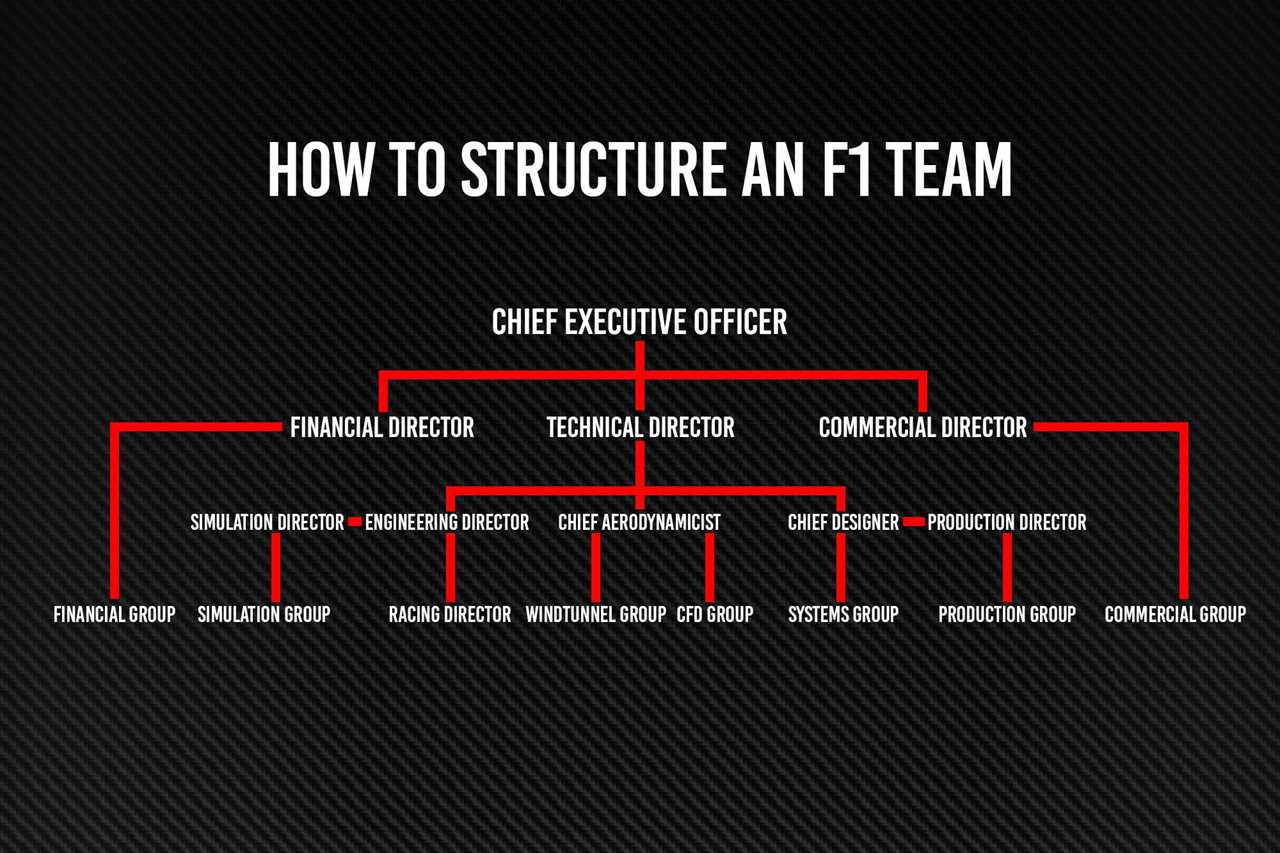

The pyramid structure is without a doubt the best. It is not just one huge pyramid, it is a number of smaller pyramids that cover all the different disciplines required to be successful. They all join up making one large pyramid in which, if structured correctly, everyone knows who is next in command and who they work for.

I have always been told that one person can only manage 10 other people efficiently, so that gives you a rough idea of how many pyramids you need to set up to cover a team of at least 600 people.

Obviously, there needs to be someone at the very top and that is usually either the team owner or, if it’s a large conglomerate, the team principal. We have seen in the past teams like McLaren under Ron Dennis be very successful as using this pyramid principle it had one person heading the technical department. But because the technical director was getting so much credit for the team’s success, this didn’t go down too well with Ron and led him to change the structure to a more horizontal line under him. This led to the so-called matrix system, which is effectively a flat structure.

This kind of thing happened quite a few times at McLaren. First it was John Barnard, then Gordon Murray and in the end Adrian Newey. It’s happened in other teams, but the really successful teams in the 2000s have stuck with the pyramid approach.

If Andretti does his homework, he will discover that this is the correct route for him to take. So first of all, set up an initial company pyramid structure compromising smaller pyramids including technical design, research and development, engineering, manufacturing, finance, commercial, media, the race team, logistics etc and try to fit them all together as laid out in the diagram below.

As the design of the car needs to start first, he needs to set up that initial pyramid structure for the technical group followed closely by the R+D and engineering groups as they all need to work together.

These pyramids work far more effectively than having a more flat structure. You need someone to have the final say, which ultimately has to be the technical director when it comes to matters of design, but as teams are so large they can’t make every single decision.

They need to look at the big picture, set the targets everyone else is working towards and allow the many pyramids below to get on with their work and make the smaller decisions amongst themselves. That will allow the technical director to ensure that everyone is pulling in the same direction and has a clear understanding of what they are working towards.

Communication is important, in that there has to be enough of it but not too much. With so many people involved, it can be too easy to spend too much time talking and meeting and not enough actually doing. That’s how politics can get in the way. So this structure, functioning properly, should work well. And that’s crucial for Andretti if it has design and development work happening on both sides of the Atlantic.

Assuming Andretti comes in for 2026 (although it could be earlier), that gives the organization three years which should be plenty of time to build it up and let it settle down. Ahead of actually racing, the team just has to focus on designing and developing one car without the complication of competing at the same time so this is a good chance for the structure to bed in and be tweaked to ensure everything is working as it should be .

If Andretti thinks he can share design or engineering staff between his IndyCar or other activities and F1, then he is being a bit naive. At Jordan, Andrew Green and myself went off engineering two of Jordan’s three F3000 cars during our design year and I can assure you, it didn’t help matters. And that was in a period where cars still had a gearstick and a steering wheel was a steering wheel, so much less complicated than the current F1 car.

Once you get into the cycle of racing every week or two, developing a current car while designing a new one for the next season is when the real stress comes into the system. So it’s essential that the Andretti organization puts together can cope with this. As Haas has shown over the years, being small is OK but improving as the year progresses is almost impossible.

I would expect that Michael Andretti would want to be involved in the day-to-day decisions but we know from his own venture into F1 as a driver for McLaren he does like to spend his free time in the USA, so he will need a sidekick that can be his voice when he is not around. Whoever that is doesn’t need to be massively experienced in F1, they just need to have a good understanding of motor racing and its requirements. I’m pretty sure that he will have someone that already works with him that he trusts for that position.

I remember when Max Mosley and Bernie Ecclestone were proposing their original $50 million budget cap, Christian Horner was running his team in F3000. We were having a chat one evening and he was asking me how he could go about setting up a team to be successful within that limit. At that time, it was to cover more than the budget cap currently does with fewer escape routes for overspending.

It is possible to go F1 racing for a lot less than the frontrunning teams spend, but when you consider the Red Bull budgets over the years they have been involved, which he put together, it shows that to be competitive you need to join the club . Very few, if any, over the last 30-40 years have been competitive with a lesser budget or structure than their direct competition. So from day one, Andretti needs to show he understands this, wants to win and doesn’t just want to be in F1 for the sake of it.

From the announcement earlier this month about partnering up with GM and having its facilities available as required, he needs to be careful in how they go about this. It can very easily be more disruptive than helpful.

It’s not impossible to make it work, but F1 is a very different beast from production cars, even high-end production cars. In F1, you get judged more or less weekly so being responsive is critical to your operation and relying to any extent on a giant like GM can very easily slow down progress.