On that day 33 years ago, the F1 world was shaken by the death of Enzo Anselmo Giuseppe Maria Ferrari. Born on February 20, 1898 in Modena, he fought for Italian honor first in the pre-war years at Alfa Romeo, then in the early years of the Formula 1 World Championship with his own brand, carefully creating the enigmatic image of a man who seldom met Participated in races or even training days and still pulled so many strings from his fortress in Maranello, where he not only created Grand Prix cars and sports racing cars, but also street cars that the wealthy public could buy.

In his day, the white-haired patrician with the dark glasses was described as mysterious, charismatic, autocratic, political, imperialist, irascible, unsentimental, ruthless and cold-blooded. He may have been all of these things at different times in a remarkable career in racing.

But one thing is certain: there was no one in sport, either before or after, who was like him. Here are five vignettes to help paint the portrait of a one-of-a-kind colossus.

Ferrari at 1000: the enduring pull of F1’s most iconic brand

A photo of Enzo Ferrari around 1950, at the wheel of one of his earliest racing cars

How good was he a driver?

There is still considerable debate about Enzo Ferrari’s career as a racing driver. He’s featured in some honorable books as a grands prix competitor, but although he was on entry lists for the 1922 Monza, 1923 Mugello, 1924 Lyon (and 1930 Mille Miglia) races, the best evidence is that he didn’t appear in one of them.

Mostly he competed in Italian races, and his greatest achievements were winning the Coppa Acerbo in Pescara in 1924 and second place at the Targa Florio in 1920. His other events were only regional hill climbs and local road races according to historians like Griff Borgeson and Brock Yates.

PODCAST: Jacky Ickx on Stewart, Brabham, the great Enzo Ferrari and more

Enzo Ferrari (R) with Nicola Romeo (M) and Giuseppe Morosi (L) in Monza 1923

After the deaths of Ugo Sivocci in Monza in 1923 and Antonio Ascari in Montlhery in 1925, he got involved with the highly competitive works of Alfa Romeo under the aegis of Scuderia Ferrari from 1929 and later as team manager when Alfa regained control Names 1937.

But it wasn’t until he started building cars under his own name in 1947 that the legend took shape, which is still alive today. When they defeated the Alfa Romeos at Silverstone in 1951 to mark the end of an era, he theatrically declared: “I cried for joy. But my tears of excitement mixed with those of sadness because I thought, ‘Today I killed my mother’. “

READ MORE: Under the body of the Alfa Romeo ‘Alfetta’ – 70 years after it won the first ever F1 race

Charles Leclerc and Ferrari team principal with the Ferrari 375 F1 at the 2021 British Grand Prix – 70 years after the brand’s first F1 victory

Ferrari’s personal favorites

Enzo Ferrari had many star drivers in his team in his day: Juan Manuel Fangio won one of his five titles with him in 1956; the very first champion, Giuseppe Farina, moved from Alfa Romeo to his stable; Alberto Ascari, who is equal to Fangios, won his first titles in 1952 and 1953; Mike Hawthorn won his first race and the only title for Ferrari; Phil Hill, John Surtees, Niki Lauda and Jody Scheckter won their titles in the red cars, while other stars like Dan Gurney, Richie Ginther, Cliff Allison, Wolfgang von Trips, Ricardo and Pedro Rodriguez, Chris Amon, Derek Bell, Jacky Ickx, Clay Regazzoni, Mario Andretti, Didier Pironi, Patrick Tambay, Rene Arnoux, Michele Alboreto and Gerhard Berger adorned Ferrari cockpits.

Unfortunately, Eugenio Castellotti, Luigi Musso, Peter Collins, Lorenzo Bandini and Ignazio Giunti died in the race for the team.

READ MORE: F1’s Best Drives # 5 – Fangio’s Race of a Lifetime

Alberto Ascari (L) with Enzo Ferrari and Mike Hawthorn (R) in 1953

But long before Red Bull’s Helmut Marko gained the reputation of being tough on his drivers, Ferrari was considered the “agitator of men”. He preferred not to name a number one driver, but rather pit each of his pilots against each other to establish a natural pecking order.

After traveling all the way from the UK to Bari in 1951 to drive for the team, only to find on arrival that he had been “replaced” by Piero Taruffi, Stirling Moss refused to ever drive for Ferrari.

Niki Lauda was outraged to discover that he had recovered so amazingly from his near-fatal burns at the Nürburgring in 1976 that he was replaced by Carlos Reutemann. He insisted on staying, won the 1977 World Cup, then promptly left for Brabham.

But Ferrari had two favorites: pre-war ace Tazio Nuvolari and post-war legend Gilles Villeneuve. He loved the way they both fought no matter where they were in a race. He called Nuvolari the best he had ever seen and loved Villeneuve’s never-say-die attitude, saying of him: “He made Ferrari a household name and I liked him a lot.” That was really praise from Enzo Ferrari.

READ MORE: 5 Reasons F1 Fans Still In Awe Of The Legendary Gilles Villeneuve

Enzo Ferrari made no secret of his love for Gilles Villeneuve

Old beliefs about engines and chassis, but an aerodynamic innovator

Enzo Ferrari firmly believes that a racing car’s engine belongs in the front of the chassis, much like the horse that pulled the cart. It was typical of his ingrained views on technology, and it took a lot to convince him to develop the Dino 246P in 1960, the first rear-engined Ferrari Grand Prix car.

It wasn’t a success, but after Phil Hill scored the final triumph for the front-engined F1 car at Monza that year – the man who was fondly called Il Commendatore, Il Drake, or l’Ingegnere – he had a rear-engined car ready for the new 1.5-liter formula from 1961, which promoted the American to the world championship title.

Even so, Ferrari stuck to old ways and technical director Mauro Forghieri had to use all his skills to develop the wings that first adorned F1 cars at the 1968 Belgian GP.

Others had used such devices elsewhere, notably Michael May and Jim Hall in sports cars, but Ferrari, along with Lotus and Brabham, was for once at the forefront of the aerodynamic revolution when the word “downforce” entered the F1 lexicon.

The Ferrari 312 with Jacky Ickx at the wheel won the 1968 French GP in Rouen with an attached rear wing

Ferrari, the master manipulator

Ferrari was always a master at getting what he wanted and usually won the political games he played from time to time. If he occasionally missed races, strikes in Italian metalworkers’ unions were usually blamed, though that became a weaker excuse after John Surtees introduced the team to fiberglass instead of aluminum for things like bodywork.

The 1986 Indianapolis project became a case in point, although some within the project, such as Piero Ferrari and Bobby Rahal, insist that the Ferrari 637 should really be racing in Indianapolis. And to be fair, it seemed like a great length just to get a political point …

PODCAST: Drivers Strike! The inside story of the Grand Prix when the drivers refused to drive

Here is what happened. This year the FIA was planning the next Formula 1 formula to replace the 1.5-liter turbo cars. This formula was practically a hangover from 1966 and was cleverly exploited when Renault opted for the almost forgotten 1.5-liter “blown” option instead of the previously universal 3-liter naturally aspirated engine.

For 1989 it was planned to continue only with the 3.5-liter Atmo engines that had been approved since 1987, but with only eight cylinders. This infuriated the old man who valued his V12s.

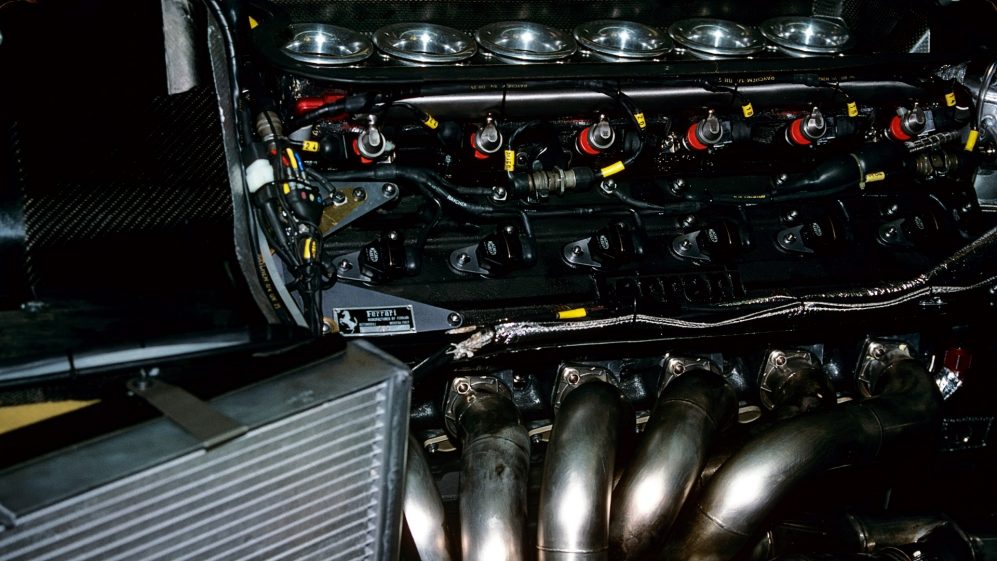

Enzo Ferrari was a passionate proponent of V12 in F1. Above is the cylinder bank of the Ferrari 642 in 1991

To express his dissatisfaction, he published an absurd statement: “The news of the possibility of Ferrari giving up Formula 1 to drive in the US has a fact. Ferrari has been investigating a participation program in Indianapolis and in the CART championship for some time.

“We talked about the possibility of driving CART to show that we won’t necessarily be in F1 forever.”

That hidden threat was enough to make the FIA’s will subordinate to its own, and 12-cylinder engines remained part of the F1 for a while.

But the 637 designed by Gustav Brunner had been built, and Bobby Rahal was testing in Fiorano. The Indy star insisted it was more of a serious project than a political tool, but today it’s an unprecedented museum tool – the removal of which could possibly have been in exchange for the continued legality of V12s – that illustrates how Ferrari could build everything works to its advantage.

Ferrari’s unused CART prototype, the 637, in the Ferrari Museum in Maranello

The miracle race of memory

Ferrari’s 1988 season was less than brilliant as Senna and Prost’s McLaren Hondas went amok. But then something strange happened at the Italian Grand Prix in Monza, just 28 days after Enzo Ferrari’s death.

Prost led initially, then chased Senna hard despite a misfire that led to his resignation. Then Gerhard Berger and Michele Alboreto were gradually able to keep the Brazilian under pressure in their Ferraris because he had to save fuel. Senna pushed hard to maintain his lead, tripping over the Williams of backmarker rookie Jean-Louis Schlesser as he lapped him in the first chicane with just two laps to go and landed as he spun.

READ MORE: Remembering an emotional Monza 1-2 for the Scuderia

The crowd went wild as the two red cars took first and second place in an emotional tribute to their creator, almost as if he was pulling the strings again for the benefit of his beloved team. It was, after all, the only race that year that McLaren couldn’t win …

Ferraris 1-2 at the 1988 Italian Grand Prix

In Berger’s winning car, it took four runs to measure the fuel – initially it was 151.5 liters of fuel, which exceeded the maximum permitted amount of 150. A second and then a third refueling before only 149.5 liters could be persuaded into the tank and the car could be declared legal. Unaware of the drama, the Tifosi had already invaded the track, waving their Ferrari flags in madness.

That night the church bells in Maranello rang even louder at their traditional celebration of a Ferrari victory. And somewhere, perhaps an old white-haired man with dark glasses was smiling his enigmatic smile again.

LISTEN: What it meant to drive for Ferrari under Enzo, from Andretti, Scheckter, Berger and more

The post A portrait of a unique colossus – 5 stories about Enzo Ferrari, 33 years after his death first appeared on monter-une-startup.