The scale of these changes meant that F1’s traditional development battle is no longer the one-horse race that it’s been in recent years. Teams are having to find incremental performance gains from a host of different avenues this year.

F1 had essentially become one dominated by aerodynamic endeavor, with brakes, tyres, suspension and setup well-honed and understood after years of the same regulatory framework.

Instead, they’re now presenting intriguing, diversionary development strands, both at and away from the race track, as the knowledge that teams had accrued over the course of the last decade or more has been completely eroded.

This has required the teams to not only redesign parts to comply with the new regulations but also search for ways to improve their performance based on the new parameters and how they interact with each other.

2022 brake disk dimension

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

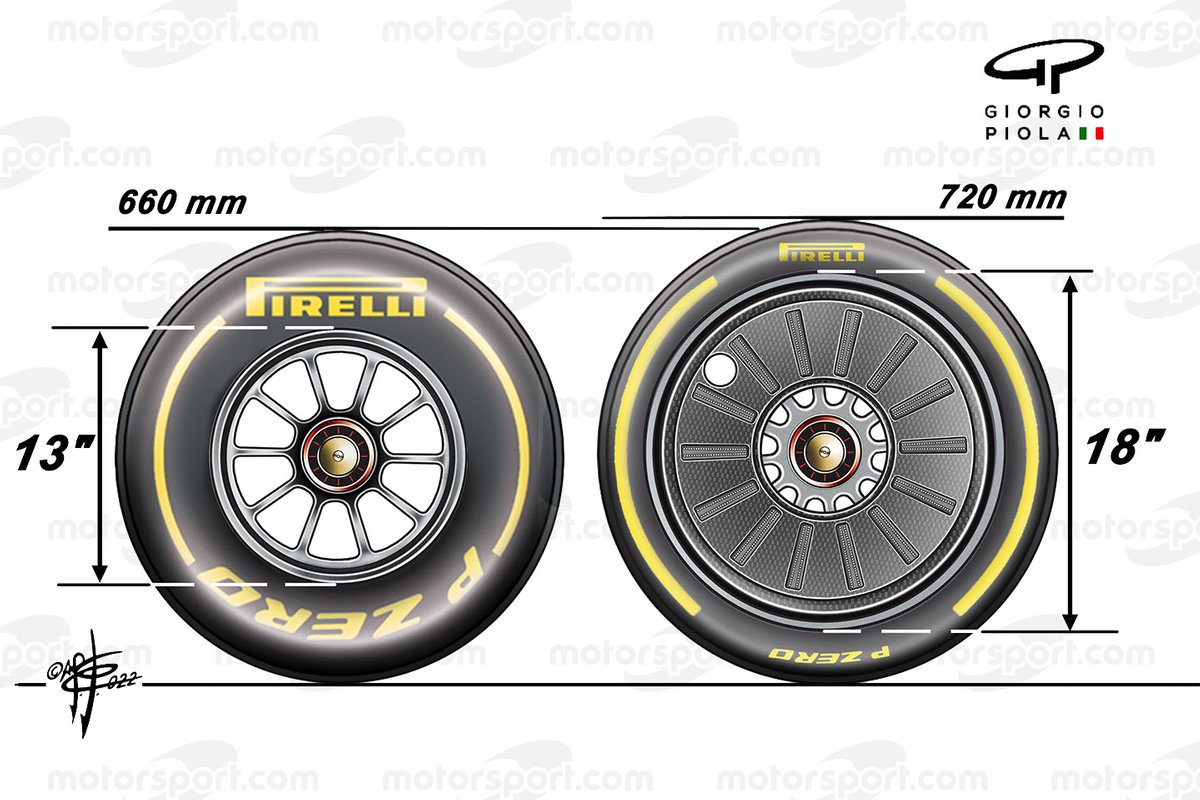

Tire dimension comparison

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

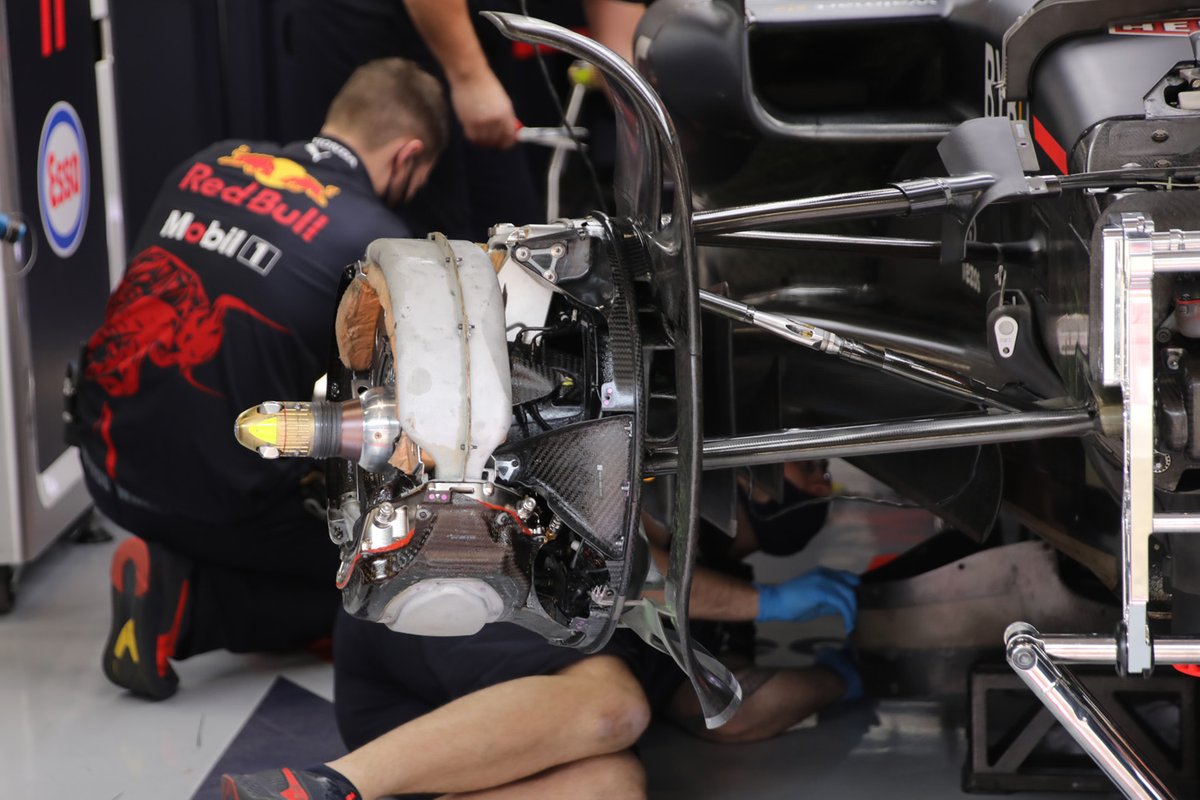

One example is the brake assembly, which has been altered significantly not only in order to fall in line with the switch to 18” wheel rims, but also as a consequence of some of the tricks teams had used in the past being taken away from them .

Previously they’d found ways to balance the design of the assembly, with the primary function of cooling the brake components, with aerodynamic assistance and transferring heat to the tire via the wheel rim.

The regulations have been devised in such a way that the ancillary functions now take much more of a backseat. But that’s not to say the teams aren’t devising ways to bridge the gap.

For example, both Red Bull teams and McLaren have taken to enclosing the now larger brake discs in order to better manage the dispersion of heat within the assembly and how this is transferred to the wheel rim and tyre.

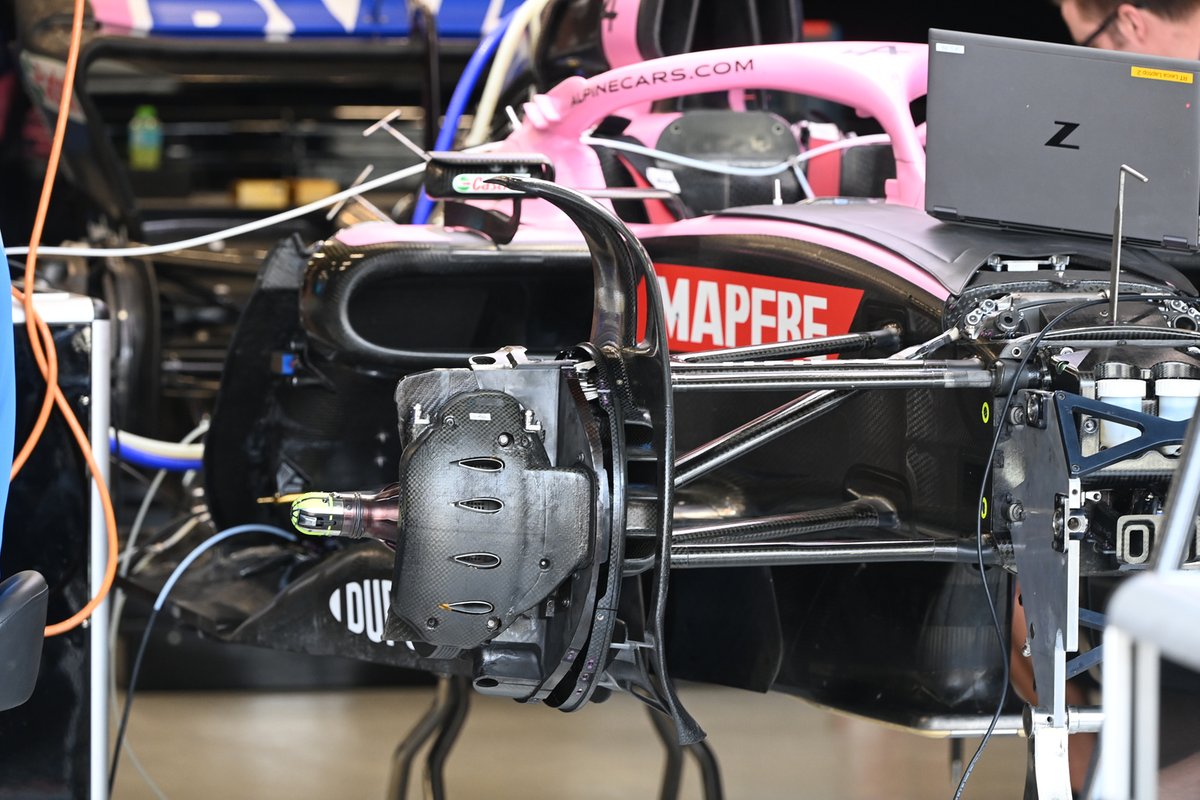

Meanwhile, several teams have also returned to the more traditional front mounted position for their caliper. It had previously been moved to a more rearward position to facilitate the use of aerodynamic channels to divert air out through the feel case.

In Alpine’s case, whilst wrapping its caliper with a carbon fiber duct to supply cool air to the component, it has also opted to include teardrop-shaped outlets. These provide some of the heat created by the brake disc drillings a route in which to take in order that it doesn’t create heat soak.

This will undoubtedly be an area where the teams continue to search for performance though, as it’s a sensitive junction at which several parameters can be affected.

But, with the limitations posed by the regulations and specification of wheel rims and wheel covers, there’s clearly a more finite curve.

Pirelli tyres

Photo by: Motorsport Images

The introduction of a larger wheel rim and lower profile tire has long been on the agenda for the sport, with the outgoing 13” wheel diameter considered a relic of the past given the ongoing trend to increase wheel rim sizes on road cars.

Whilst teams and drivers had a taste of what was to come when they tested the product on mule cars during testing last season, they’re still on a steep learning curve when it comes to finding performance.

It’s a quest that is difficult due to the small quantity of data points at hand, with feedback from the drivers a critical factor in unlocking performance in these early stages.

The change in operating parameters for the tires are also having an impact, with Pirelli reducing the maximum temperatures of the tire blankets, from 100C to 70C for 2022. They are also holding the minimum inflation pressures relatively high at each event, so far.

Coupled with the physical changes to the tyre, these have an impact on the temperature curve, with teams having to adjust to how the tread and bulk temperatures are affected and what effect this has on performance and degradation.

Furthermore, the dynamic behavior of the tire has been altered, which not only affects how the aerodynamicists model the tyres, it also requires the driver to alter their style in accordance with how the tire migrates under the various loads and stresses it will endure during the course of a lap.

Red Bull Racing RB18 detail

Photo by: Uncredited

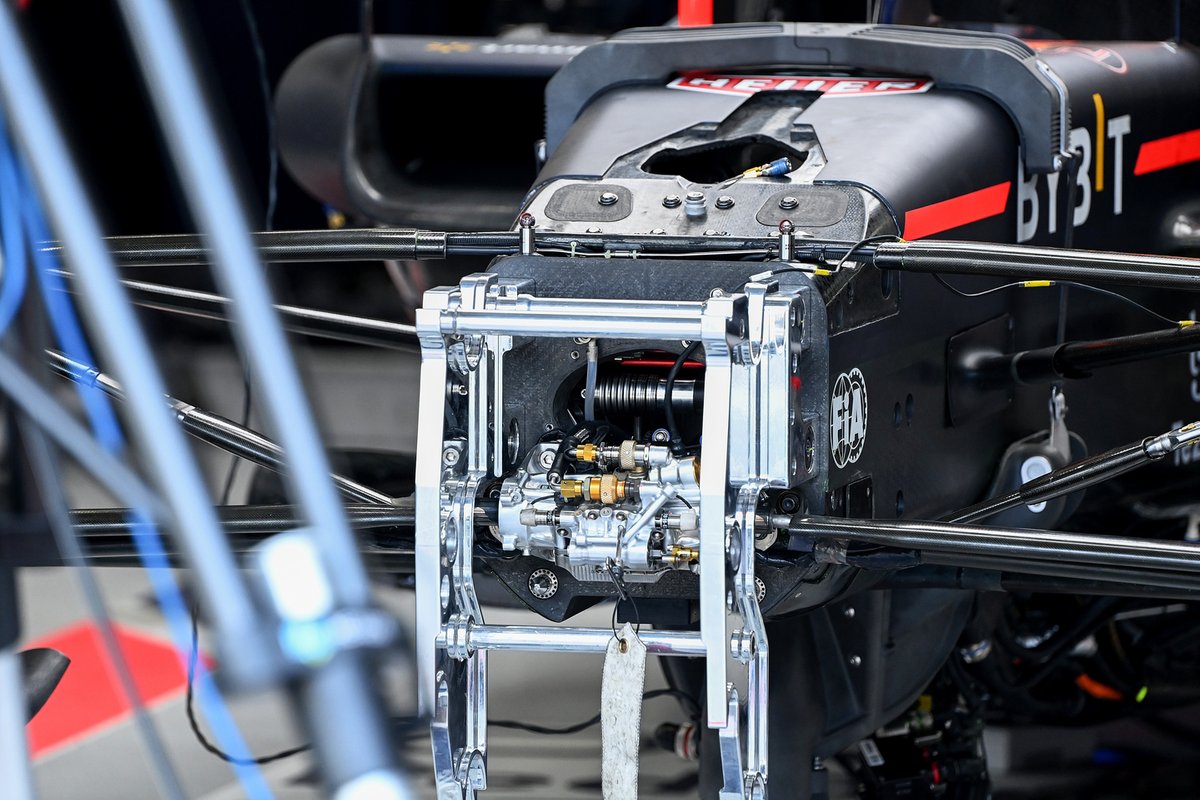

Managing these loads and stresses has been made more difficult in 2022, as aspects of the suspension’s design that had become a staple over the last few years, including hydraulic elements and inerters, have been ruled out.

A reduction in these compliance tools is also worsened by the need to run the car as stiff as possible in order to take advantage of the switch to a more underbody-dominant aero platform.

The requirement to run these cars as low and as stiff as possible lends itself to the parts needing to be able to withstand more stress, whilst the budget cap has also pushed teams towards building parts that are more resilient in order that their lifespan is increased.

This, along with the weight increases associated with the larger wheels and tyres, the addition of the wheel covers, tethers for the rear wing, a front anti-intrusion panel and more rigorous tests for the front and rear crash structures, has all led to an increase in the cars’ weight.

As a consequence, the FIA upped the minimum weight to 795kg for 2022, with a further 3kg offered as light relief just ahead of the season opener, along with the ability to add stays to the rear section of the floor.

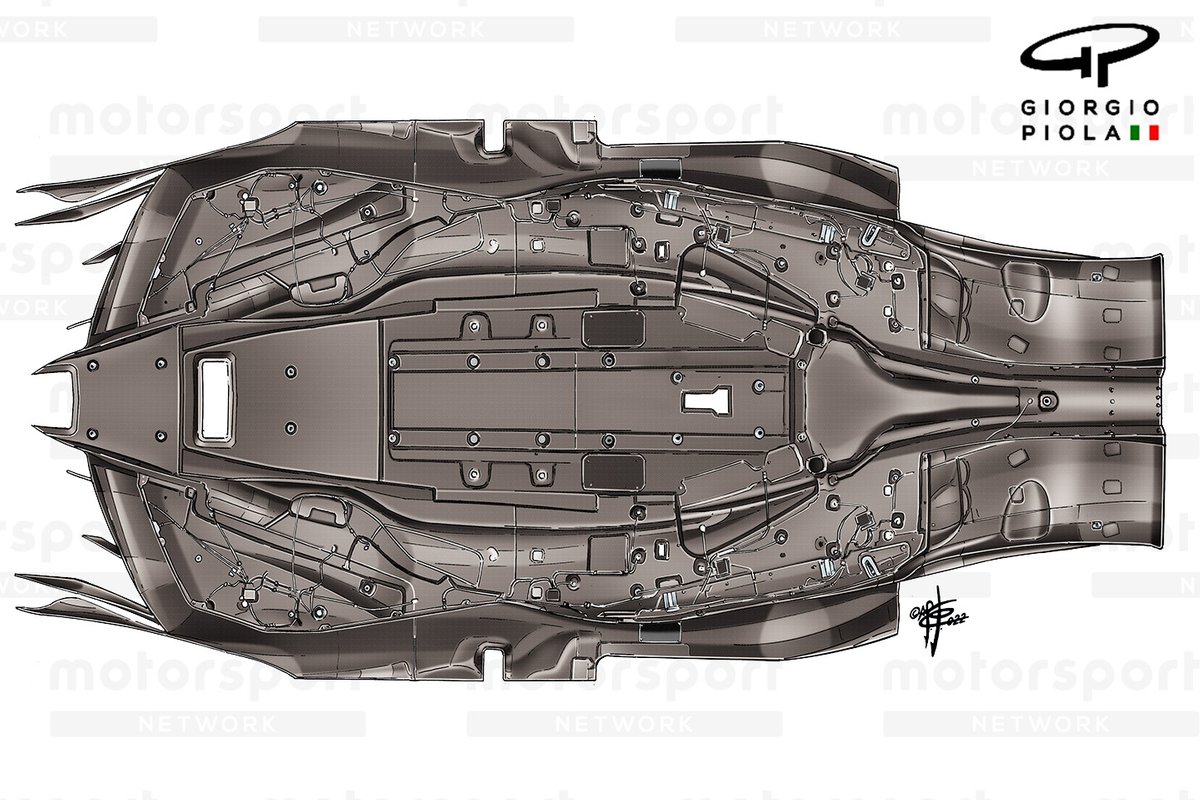

Without these extra stays, the teams struggling the most with porpoising would have suffered somewhat of a headache had they not been allowed, as the floor flexing was clearly worrisome when it came to reliability.

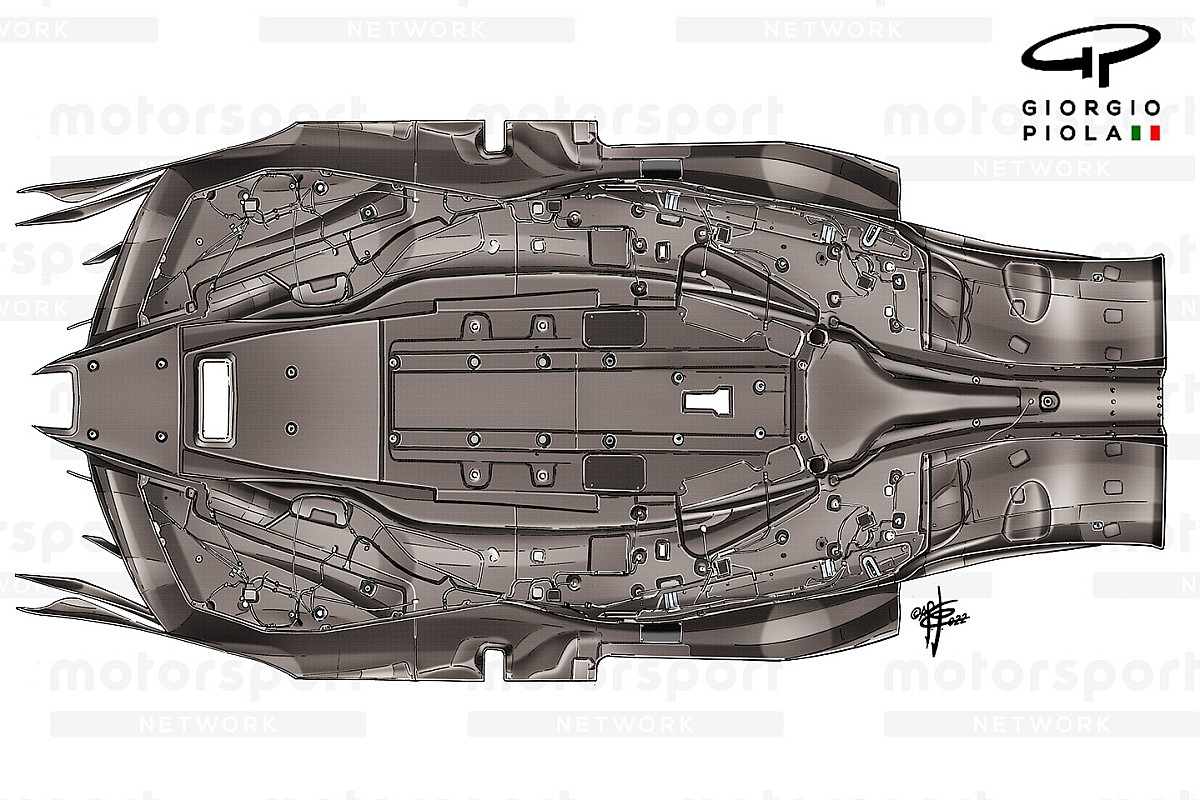

Red Bull Racing RB18 floor detail

Photo by: Giorgio Piola

The introduction of the stays offered some respite for those that were struggling with the flexing issues but also offered everyone a means to offset the load imparted on the floor, resulting in teams being able to redesign their floor for aerodynamic gains, whilst also offering a means for them to save weight.

It’s understood that some teams will save several kilos in this regard as fresh parts are brought to the forthcoming races.

There’s also a trend appearing that’s seen teams sacrificially looks in order to reduce weight, as the cars are left with more and more carbon fiber exposed.

Teams have been doing this for a number of years, in fairness, but this year it seems to have been taken more seriously as the teams continue to look for ways to save even a few grams, in a bid to beat the bloat.

Williams’ latest makeover, in Melbourne, consisted of paint being stripped from their front and rear wing, a section on the nose tip and two lines extruding up the side of the nose from it, the outer, ramped section of the sidepod, a portion of the chassis that blends into the halo mounting and a large section of the engine cover, including the mini shark fin.

Williams is not on his own either though, as Aston Martin and McLaren had already stripped paint from its engine cover. Red Bull and Mercedes lost paint from its front wing and most, if not all, have adjusted their livery in some way to help reduce weight where they can.

No silver bullets

In the past, large scale changes to the regulations have often led to an early development battle where a standout solution has been devised that requires immediate adoption.

The framing of the new regulations appears to have prevented this, with teams more concerned about resolving any inherent behavioral issues, such as porpoising, in order to find performance, rather than looking for a bag of magic beans.

Standing still, in terms of development, has always been seen as a weakness in the past too, with ongoing development seen as a way of progressing the project forward at a more rapid rate, even if that means a few missteps along the way.

However, with such a steep learning curve on how these cars extract performance and the budget cap and sliding scale resource restrictions creating a very different outlook on how teams go about their development, standing still could be the new going forward, especially if performance is unlocked that a competitor doesn’t happen on with their own car.

Meanwhile, the calendar is also having a bearing on the teams’ decisions when it comes to development, as the Spanish Grand Prix has traditionally served as the first major developmental waypoint, due to the logistical efforts required to deliver larger parts to flyaway races.

However, with Barcelona now sixth in the queue, rather than fifth, you might have expected teams to have arranged for updates to arrive at Imola, given it’s the first European round of the season.

Introducing any major updates might be considered foolhardy though, as Imola is a Sprint weekend, which means that the teams only have a single practice session on the Friday.

Teams will prefer to spend their time honing their set-up during that one hour window, rather than plow time into evaluating and understanding a vast array of new components in a condensed time frame.